There Were Chinese In The South?

There Were Chinese in the South? This is already a theme in my website, about not being aware or taught much about Chinese American history, much less Asian American history. I know we can say that such history is still not truly in the mainstream today, though some states have made efforts to include Asian American History as a part of their curriculum. Not my State of Missouri.

This Blog is about a fascinating topic of….A History I Really Never Knew.

Growing up, I certainly did not know or have any reason to think that there were Chinese in the South. This is a horrible thing to admit. But it seems like all anyone wanted us to focus on (or learn) in history about the South was the Civil War, where the schooling was of course about the evolution of a country, our history of slavery and the many other causes of the War. But my lesson plans seemed to be more about the battles and generals, yet few depictions about the impacted people or the human details about the Reconstruction Period. Certainly, no mention of the Chinese who were a part of this Reconstruction. I’m pretty sure I wasn’t taught this (remember, I hated history and may have been nodding away in class). I would likely have perked up to hear the word “Chinese.” Even to this day, when I mention Chinese in the South, most people raise their eyebrow and say they didn’t know.

So, I will provide a little introduction about this history and some highlights and about how there are so many historical connections between the Midwest and the South. In 2024, I have become connected in so many ways with this Southern history, personally as well.

My Own Introduction….and it was not that long ago.

My first real introduction was coming across a documentary film, Far East Deep South, about a San Francisco Chinese-American family, where it is revealed to the sons that in their history there was a grandfather and great-grandfather who lived in Mississippi. Definitely a major surprise to the sons. I love the moment in the film when one son says, “Chinese people in Mississippi?” Weaved into this family discovery journey is how these Californians, often not aware of the rest of the country, also discover the U.S. on their road trip. As an aside, I can attest that I often had to explain where St. Louis and the Midwest was located when I married into my own Californian family. Recently, I have been playing that role about the Chinese in the South.

Discovering this movie was also at a time period when I was accidentally becoming a historian. I had been grasping for information about Chinese American history. While the southern geography part did not resonate, it did perk my interest. But I certainly could relate to the Chiu Family. The sons were very much like me and my brothers, as well as my Chinese American wife from L.A. We were all born here, Americans, yet we often don’t know enough about our Chinese heritage roots here. Or we can’t complete the puzzle of what we do know. I know this is not unique to being Chinese. Surprisingly, most Americans can only describe their history within a generation or so.

Baldwin, father Charles, brother Edwin

Small World Story: Early this year I would have the opportunity to be on a National Park Service panel for the film screening with Baldwin, co-hosted by the University of Missouri St. Louis. On his visit, he would mention that he once worked in St. Louis and we would discover that a very close friend of his (college friend?) was the son of family friends of ours, who in turn worked for my parent’s company. At this screening I would meet “Emmi,” this very pleasant, softspoken woman from Memphis. I had never really been around a Chinese person with a southern accent. Another ah-ha moment. Emmi and her own family history is in the film, about her family JW Dunn taking it over.

Baldwin and me (left). Baldwin, Emmi Dunn, me, Helen Lee (right)

The Chinese in the Deep South / Mid-South

So, the Chinese in the Southern States is really quite logical. It entails the ever-present U.S. topic on the balance of commerce and labor. The Chinese history story illustrates the perpetual search to always reduce labor costs, typically though the replacement of the workforce (of the times) with the latest wave of cheaper, immigrant labor. It’s part of American history. It continues to this day, though we now outsource to other countries.

What history books rarely touch upon, is after the Civil War, with the reality coming to bear that the freed Blacks would most certainly pack up and leave, there were concerns on how the plantations would continue to function with the loss of labor.

So, in 1869, in Memphis, there would be a large convening of 500 business owners to discuss the “business” idea to debate if the contracting with the Chinese worker was a viable solution.

The Chinese Question was an often-used subject and headline. This illustration captures teh sentiments and hate.

“The Chinese Question,” a full-page cartoon published in Harper’s Weekly, February 18, 1871. (Library of Congress)

Remember, the Chinese were already established laborers for the soon to be competed western railroads. On the west coast they were increasingly viewed as a threat, by the Irish workforce (depicted in the illustration).

At the Memphis Convention, not that it was simply a discussion about business, the southerners had other concerns. They had heard stories that travelled from the west coast about these “foreigners” and “heathens,” to highlight a couple commonly used terms. Could the Chinese be reliable and controllable? Interestingly, the following article capturing the convention, by the Tennessee Baptist, also added commentary that the purpose of the convention should be civil, on point about the “business” and not about political or cultural views about the Chinese.

For more coverage about the Reparation Period, this is a nice summary from the Tennessee State Museum, https://tnmuseum.org/Stories/posts/the-story-of-chinese-laborers-and-the-reconstruction-south

With the convention passed and the debate out of the way, 1869 would commence the movement of the Chinese from the west coast to the South as contracted labor. Brokers would appear, to lure Chinese away from the coast. I assume these brokers did not educate the Chinese on why there was this opportunity.

Contracted labor is an important condition of this labor movement, for the working conditions once the Chinese were there were not always as they should have been, often with “contracts” violated. This would provide a legal “out” for some Chinese not treated fairly, who would then disperse throughout the southern states, many opening up businesses, mostly in the form of grocery stores. Owning a business would eventually provide Chinese the legal rights to remain in the U.S., when by 1882 with the Chinese Exclusion Act, laborers would be banned, but business owners permitted to stay. A loophole? The Chinese are coming.

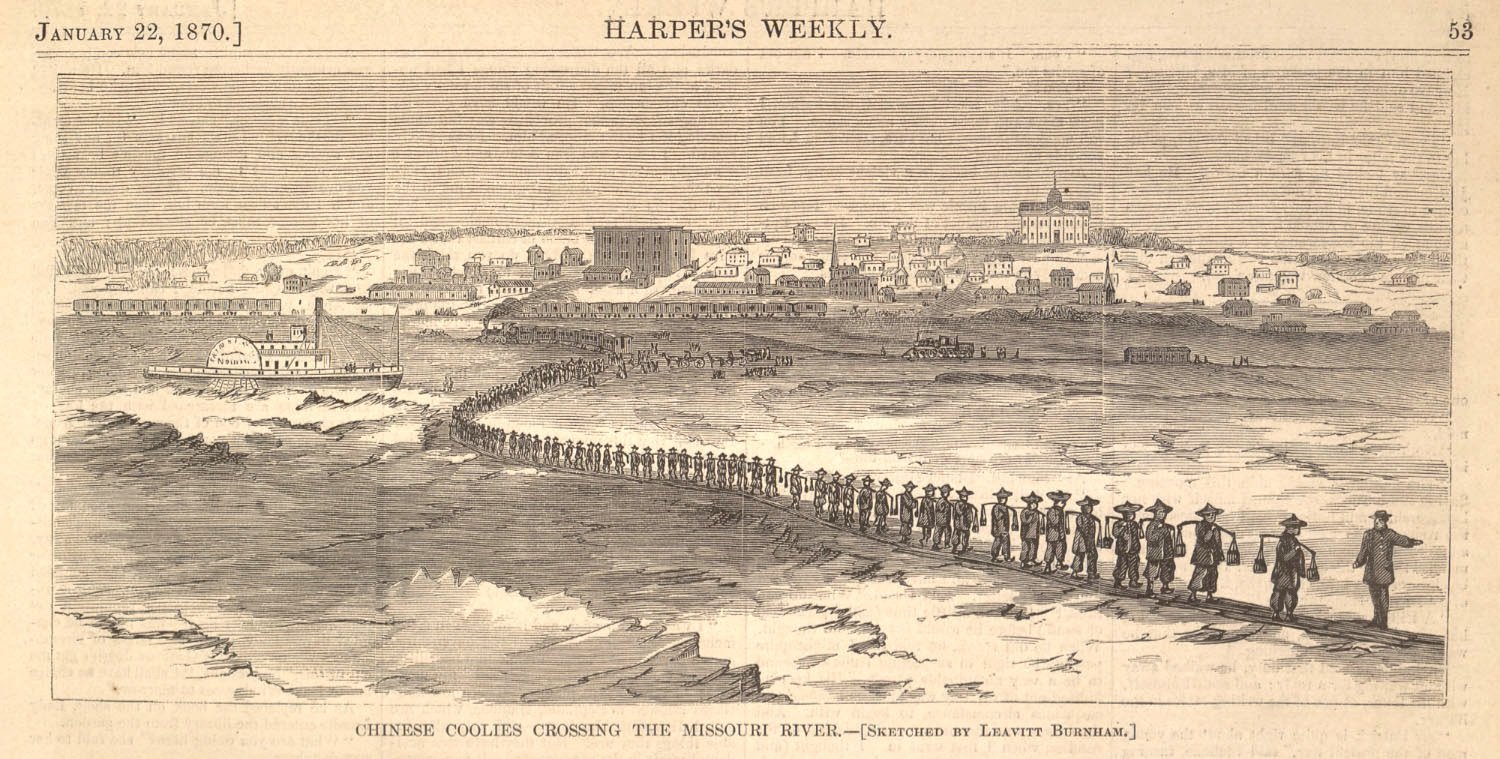

The St. Louis Connection. We discover St. Louis would become a transportation hub for the Chinese, receiving trainloads from the west coast, then either switching to another rail line or ship down to the south via the Mississippi river. One early group of this migratory movement was well documented and followed. This illustration captures the transfer of Chinese at the Council Bluffs-Omaha–Missouri River juncture, on their way to Texas via St. Louis.

In this St. Louis Republican article below, John Chinaman has Come, we learn about the first arrival of the Chinese travelling to the South. Through articles like this, we piece together history. We learn that they arrived at our Union Station and with their anticipated arrival, people had gathered to observe these peculiar people with their unique attire and their long queues (pig tails). They would then make their way down to the riverfront, about a mile’s walk. Along the way they would pass a yet to be called “Chinatown” but those Chinese in St. Louis would be slowly building up this neighborhood. Our well documented early Chinese man, Alla Lee, who arrived pre-civil war in 1857, would be a (volunteer?) helper to these fellow Chinese travelers from his common homeland.

Ironically, while the 1871 “The Chinese Question” illustration was depicting the Irish immigrant concerns about the Chinese taking away jobs, Alla Lee would marry an Irish woman in St. Louis.

So that was the big historical story back then and how, in 1869, the Chinese journey to the South started and eventually established.

Collaborations and Connections

Concurrently, many of us contributing to the Missouri Historical Society (MHS) Chinese American Collecting Initiative here in St. Louis have made endless discoveries of Chinese individuals and families here having come from or going to the Southern states. There is still so much to untap and piece together. And this cannot happen in isolation.

What is so energizing now is the breadth of research being conducted amongst many organizations and individuals through the Southern States. And, there is now communication, cross research and sharing of information to complete the narratives of this important American history. And friendships are growing.

Earlier this year was the Chinese American Histories of the South conference in Conway, Arkansas, hosted by the University of Central Arkansas, bringing together the Chinese American community, with representatives from Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, Texas and Missouri. A small contingent from St. Louis was fortunate to have attended. It was the start of our efforts to better understand this history. A tip of our history cap to Dr. Zach Smith from UCA for orchestrating this Conference.

While at the conference, I would learn a more modern fact, of a young, Chinese American man who would play a significant role of the design for buildings in Memphis as well as a well-known building in St. Louis, the Pet Milk building. This building is an oft cited example of the “Brutalist” Style of Architecture, where the otherwise functional material of concrete is left exposed and celebrated and used for its aesthetics. There was another leading Chinese American architect at the firm, Francis Mah. Interestingly, the founder of this firm, A. L. Aydelott & Associates, was born on a plantation in Arkansas in 1916.

Only a month earlier, I had met Emerald “Emmi” Dunn a devoted leader and historian with the Chinese American Historical Society of Memphis and the Mid-South. She had come to the National Park Service event to meet Baldwin Chiu. Now, she was presenting at this conference enlightening us all.

Emmi’s family history and one of her connections is about her father, J.W Dunn taking over the grocery store originally belonging to Charles J. Lou, Baldwin Chiu’s great grandfather. At this conference, the Grocery Stories offered fascinating insights on how the Chinese figured out how to remain in the U.S. and how Chinese and Black Communities lived side-by-side (in their redlined district) and came together where the store became community gathering spots.

Left photo: Me, Emmi, Chris Gordon (Missouri Historical Society), Right photo: me Melody Yunzi Li (U. of Houston), Matthew Tao.

I would also learn at this conference how history and seeking identity was impactful in the life of a young Chinese American artist, Thandi Cai, to make a forthcoming documentary, Bluff City Chinese, with their mentor, Emerald “Emmi” Dunn. It tells the story of the nearly 150 years history of the Chinese in Memphis. Emmi has also faced her tiresome question, “Well, I didn’t know there were Chinese in Memphis?”

It has since premiered at the Indie Memphis Film Festival 2024.

Not known to many, but a fair amount of history is already captured about the Chinese in the South. The Mississippi Delta Chinese Heritage Museum on the campus of Delta State University (Cleveland, Mississippi) is a leader in this area. This PBS special provides additional insights.

PBS – The Legacy of the Mississippi Delta

https://www.npr.org/2017/03/18/519017287/the-legacy-of-the-mississippi-delta-chineseBS

So, Now What and What’s in Store?

Since this event, many of us have found ways to be connected, supportive and collaborative. It serves no purpose if you are doing your own research and keeping information to yourself that may benefit effort by others.

Many of us meet up regularly virtually or by email for thoughtful discussions, passing on tips about the histories we have uncovered that may have relevance in our respective South/Mid-South geographic areas. Regarding my interests (and the MHS Chinese American Collecting Initiative) the Southern History is completing many of our local research, stories and even solving mysteries.

Big picture, we have constructed some visions for how our work can be more integrated with the mainstream public, to educate, to have them engaged, but more so to inspire. Too much of the Chinese American story is confined to the U.S. coasts. Yes, it all began there, but there are a lot of years (with stories) that have accumulated throughout the U.S. over this 200+ years of history. History does not flyover.

Stay Tuned for more Chinese in the South news!