1957 AND a few OTHER DATES

Calendar dates are informative, revealing….and troubling

At Face value, calendar dates appear to be inclusive, in that they are shared by us all.

In the historical context, dates mark a moment in time and that moment may have importance. However, it is the designation of “importance to whom and why,” that makes it informative, revealing and sometimes troubling.

From this perspective, the particular date may actually not be so inclusive after all. Or the meaning of the date is such that we may wish to be no part of it or no desire to recognize it simply because someone deemed it important.

We often apply our own meaning (or relevance) to an individual date. But if we connect these “dates” with others, they can provide us with some greater understandings. Such as why we are where we are today, or more deeply, how “others” and their beliefs shaped us.

So, l begin this identification of a few dates (including some historical moments) that may have influenced or shaped my life, along with some trivial facts. These dates, at least, make me think what it means to be an American, of Chinese Heritage.

1957: Our Birth Date – We Have No Say. Our life journeys all begin with one classification of dates we all have in common, our date of birth.

I, for one, have never felt much deep nostalgia for my birth date or any real need to celebrate it. I rather celebrate life. I had no choice of this date. I just popped out. Nevertheless, my birth was apparently a topic (and story to tell) within my own family.

I was a “Preemie.”

Yes, I did pop out 5 weeks early in fact. I am told I had to stay in the hospital where I would be visited daily and live in a glass box (incubator}. I would be weak, only tolerating goat’s milk and weighed only 4+ pounds. So, since I am an architect and a visual guy, I had to look up what was the equivalent weight of a familiar consumer item. Disclaimer: I’m not endorsing the products, but have used them.

While all of this is overly unimportant and personal, the “incubator” topic brings me to a connection to a 1904 historical discovery of mine.

Did you know that in the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis (aka the Louisiana Purchase Exposition), where the theme was to celebrate U.S advancements on the global stage, there was a failed Baby Incubator Exhibit demonstrating purported scientific advancements? Apparently, this was just a sideshow commonly seen in other expositions, like a travelling circus. One problem in the St. Louis exhibit, a very high number of babies died. Could it possibly have been the reported 105 degrees temperatures (yep, you heard correctly)? These were glass ovens.

I only recently learned this, as I was invited to contribute with a chapter in the forthcoming book, The Wonder and Complexity of the 1904 World’s Fair, for the recently reopened World’s Fair exhibit at the Missouri History Museum. The book theme is revealing little known (or not strongly told) facts and stories and I present the even lesser known or told stories, from the Chinese viewpoint.

Some Dates I Never Knew and Why It Might Matter to Me or You

So let me highlight some other dates I discovered or was never taught, in my journey of researching and writing about Chinese American history. Some may question why such dates about the Chinese (and other Asians) in America, over 149 years ago might matter. It is less about the date, rather, revealing the deeper, often dark sentiments that were associated with an era and society.

We all know that past sentiments (and their associated prejudices) often get carried forward in society, for decades or centuries. These sentiments are often misinterpreted and used out of context, even though the era and societal views have completely evolved and changed. Weaponizing. Sound familiar in 2024?

1875: The Page Act of 1875 was a precursor to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. I was never taught this. This Act was one of the first “restrictive” laws that would prevent immigration from Asia, Japan, the “Orient,” but mainly targeted Chinese Women. The portrayal, or “pitch,” was that All Chinese Women were Prostitutes. Of course, this was a very unfair, broad claim. For, somehow there was no such singling out of all the other fine prostitutes, with international pedigrees.

Fact: Prostitution was actually not illegal in the American West and was in fact, in financial jargon, a growth industry, set up to boost the morale of the lonely, male workers of mining towns and railroads.

At first glance, this Act seems to not be unreasonable, to prevent human trafficking and forced prostitution. But when we overlay the context of extreme anti-Asian rhetoric and violence during the late nineteenth century and understand the history, the underlying (hidden) intent and impact is clear, to keep out Chinese (and Chinese women). In this case, characterizing the notion that Chinese people were morally inferior and a danger to American society.

How does such a law or actions affect me or you in 2024?

Maybe not directly, but it does become a concern when such actions evolve beyond the core reasoning, to then cause stigmatizing of a whole Race and Women. Throughout history to now, such messaging, often misused by media, leads to unfounded hatred and violence.

1882: The Chinese Exclusion Act of May 6, 1882 was the next anti-Chinese law intended to stop Chinese laborers entering the United States and to bar Chinese from naturalization. I was also never taught this. To put in the “unfair” context, the Chinese were the only race of people to be singled out by the United States for special treatment through immigration legislation. Immigration has always been a topic in U.S. History, to this very date, but singling out a Race? Sound familiar?

President Chester A Arthur House (I found his D.C home). My Ai Weiwei photo reenactment.

Similar to the Page Act, this law did not just affect laborers, but ultimately created sensationalistic, negative views of a (Chinese) People, further stigmatizing the Race.

Political actions have societele effects that don’t simply go away even if the policy is proven to be unjust, amended or removed. They linger.

1875 + 1882 = The Case of Quok Shee

As an example of the lingering effects of the 1875 + 1882 Acts is the unjust case of Quok Shee, a Chinese woman immigrating to the US 40+ years later. Upon arrival to Angel Island in San Francisco in 1916, she would be detained, repeatedly interrogated, initially denied access to a lawyer, become depressed due to isolation. After detained for 15 months on Angel Island, a 150-page report of legalistic maneuvering, this one little Chinese woman would eventually be admitted…in 1918.

This case has been attributed to too much power being given to a single entity (U.S. Immigration) without the proper, objective guidance or oversight. The lesson here? The cause and effects of Racial Profiling. The Page Act was officially repealed in 1974, nearly a century later.

1904: This date, more so era, would reinforce the conflicting views of China as a developing country but, like the prior dates, this era created much discriminatory views and hateful views towards the Chinese presently in the U.S. The 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis captures all of these sentiments. In a forthcoming new book (December 2024) by the Missouri Historical Society, I will have a Chapter devoted to the Chinese capturing some of these Chinese (and Asian) stories.

Book Launch - December 5, 2024

1924: The Immigration Act of 1924 (aka Reed-Johnson Act) creates a quota-based system with a well-orchestrated calculation method (based on the decades old 1890 census) that would by default, restrict and discriminate against certain immigrant populations, with the goal of legally prioritizing western nations. It also targeted the prevention of immigration from Asia. Thank you, Michelle Hanabusa, and the Uprisers fashion brand for elevating this bit of history, on the 100th Anniversary of the Act.

Photos from OCA Advocates St. Louis Night Market Gala. Photography by Stampd Studio Photography (STL)

1947: Searching for an Opportunity introduces a bit of history that ultimately affects my own personal history. That is my parents, who collectively lived from 1917 to 2020.

Life in China (circa 1945). Japan Surrenders. Marine Swallow Tanker to U.S (1947)

Imagine being raised during the periods of a lingering end of a ruling (Qing) dynasty, birth of a national government, constant internal political strife, war lords, extreme social disparities and poverty, colonialist opportunists eagerly awaiting and not least, Japanese occupation, war and civil war. Not everyone’s typical life story setting.

Yet somehow, when the government presented an opportunity in 1947 to seek further education to help rebuild the country, remarkably, my parents found a welcoming, small, welcoming university in St. Louis to admit my father for graduate studies. It was not an easy family decision to leave for an unknown country. My parents would become immigrants. A full presentation of their lives can be found in the Professional Work section, in the Missouri Historical Society Chinese American Collecting Initiative.

Small World Fact: This connection to Washington University was because, by chance, my mother’s middle school classmate from the 1930s was resident there with her (faculty) husband. And btw, they were the parents of Steven Chu, the Nobel Laureate who would become the Secretary of Energy under the Obama administration.

When I fully understood this tough, complex history, where their life journey would ever change at any given moment, I then learned the true meaning of perseverance, maintaining a level of confidence and keeping optimistic, even when your surroundings seemed to be against you. I learned that my own life, while not always smooth, was so much better than most around the globe.

Examining more closely my family history, my life outlook and approach to life actually changed, then at age 60ish. I recognized my learning of these histories could be brought forward to perhaps tell relatable stories that others might enjoy and learn from.

1953 (and a few years before and after): My Parent’s Green Card

Now in the U.S., my parents would be introduced to another set of challenges of a different country, one they had not yet adopted, and a city that had very few people that looked like them.

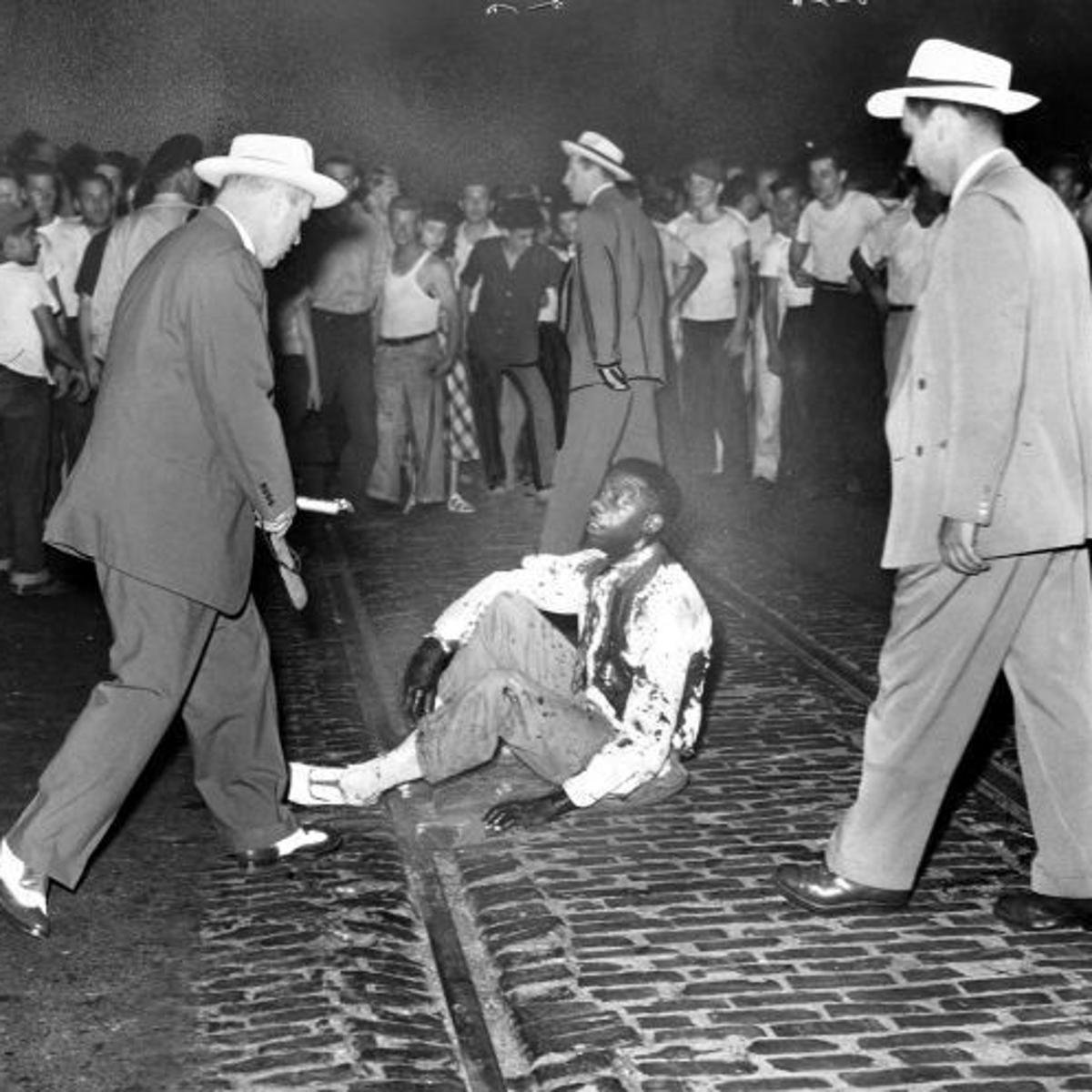

Fairground Park Protests (circa 1949). North Korean Propaganda. Rounding up Chinese Americans (1951)

Civil rights and racism, the fear of communism and a evolving country was the stage setting. Add to this the country that they grew up in was no longer a “free” country. While my father journeyed on a tanker ship to the U.S. in 1947, my mother would follow in February of 1949, 6 months before Mao would enter Beijing. The country they had temporarily left with the goal to return to help rebuild, was possibly no longer their familiar home. Their life journey was pivoting again.

Meanwhile, in this bustling new country, they found some great local welcoming, mentors and friends. They needed to stay optimistid and see where this ride would lead.

But if you understand history, the early 1950s had other implications, to a select few. China was now well engrained in Communism, prompting the ‘Red Scare’ and McCarthyism in the U.S., which would raise suscpicions (and create surveillance) of all people of Chinese descent. Then, when China aligned with North Korea, more tough decisions needed to be made, for the U.S. and Immigration Services would approach foreign born Chinese for them to declare loyalty to the U.S or to pack up and leave.

Recognizing that they may not be able to return to the present ruled China, their homeland, my parents decided to pursue staying in the U.S. And through an ingenious immigration attorney (I am only surmising), my parent’s names were slipped into a House Resolution that permitted a very limited number of Chinese to receive Green Cards. This resolution was tied into the older Displaced Persons Act of 1948. I suppose that my parents were now essentially categorized as refugees.

US House Concurrent Resolution 73 (May 11, 1953).

Had this “historic” moment not occured for the TAO Family, I most certainly would not be an Accidental Historian and sharing my stories today. Who knows where I would have ended up, or even if I would be alive at this stage of my life.

And that is what makes history and dates so interesting and troubling. We cannot control them and it can be purely luck that takes us on our paths.

As a concluding note, eventually, in 1965 the U.S. would revamp its immigration laws with the introduction of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. This new law would eliminate the National Origins Formula which was essentially a subjective, unequitable, racially discriminatory way of deciding who may apply to immigrate to the U.S. The 1965 act created a seven-category system of preferences to guide how to evaluate and admit.

And how fitting that in my youth, I would later find myself in that same city of the signing the Immigration Act with Lady Liberty and a newer World’s Fair, 60 years after that 1904 Fair that was a bit less welcoming to Chinese.

Calendar dates are so interconnected, with personal meanings.